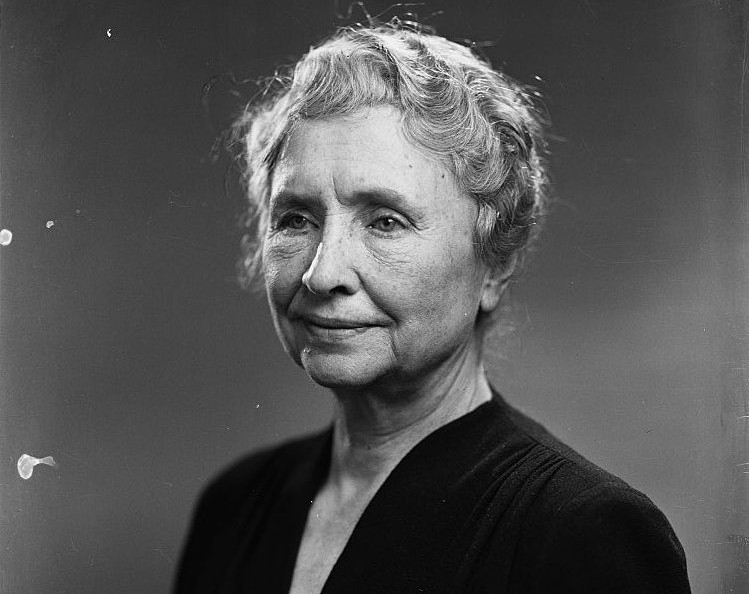

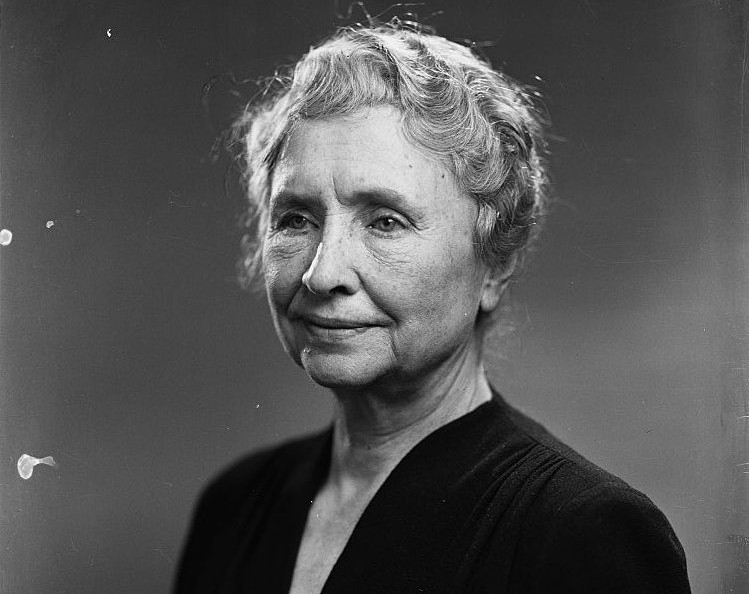

Helen Keller and the advancement of digital Braille

Born in Alabama, USA on 27 June 1880, Helen Keller lost her sight and hearing at a mere 19 months old due to an illness. In spite of this, Keller was determined to live as full a life as possible, and learned how to communicate under a teacher from the Perkins Institute for the Blind.

This teacher was Anne Sullivan, then 20 years old and partially blind herself. She made her teaching breakthrough with Keller by making the hand sign for the word ‘water’ on the young girl’s palm and running water over it – this combination of finger spelling and the sensation of water itself allowed Keller to make the connection between words and the world around her.

Keller’s vocabulary and knowledge only grew from there. She communicated mainly through finger spelling and later learned how to speak through Tadoma, a manual sign language which allowed her to lip read by feeling the movement of someone’s lips, throat, jaw, and nose.

Another form of communication Keller used was Braille. The Braille system is tactile, representing letters through a raised dot alphabet. At the time, Braille was difficult to produce in large quantities because it needed to be printed on paper. But as technology progressed, innovative solutions combining traditional Braille with digital devices were created. Today’s refreshable Braille displays and electronic notetakers give individuals who are blind the chance to write and read digital content in real time.

Users can even connect their Braille displays to a tablet, computer, or mobile device and translate Braille to speech output, thus expanding their ways to communicate. Modern Braille displays have become more compact, lightweight, and affordable than ever, enhancing portability and accessibility.

Among many other adventures, Helen Keller and her companions, Polly Thomson and Anne Sullivan – whose parents hailed from Limerick – toured Britain and Ireland in June 1930. Not only was Keller the first deaf-blind person to effectively communicate with the sighted and hearing world, she was also the first to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree!

Throughout her life, Keller worked tirelessly to advocate for people with disabilities. Digital Braille technology is a testament to her determination to navigate a world which was once limited to her, and it continues to improve everyday. It is a powerful tool that empowers people with visual impairments and strengthens their participation in education, employment, and daily life.